“This sacred site represents our living culture and more than 5,000 years of our history. We will not allow our ancestors to be disturbed.”

—Joint statement from Ohlone family bands

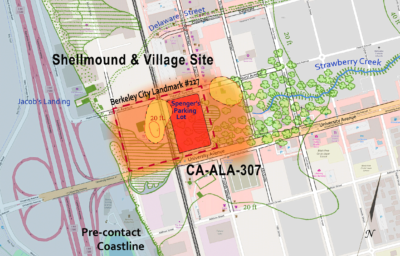

Beneath the pavement in West Berkeley dwells a cultural and historical touchstone of singular significance: the first human settlement on the shore of San Francisco Bay, established 5,000 years ago. There, at the mouth of Strawberry Creek, the ancestors of today’s Ohlone people created a unique lifeway between land and sea. For countless generations, they practiced ceremonial traditions and constructed a great mound in which they buried their dead—the West Berkeley Shellmound.

The last remaining undeveloped portion of this heritage site, held sacred by the contemporary Ohlone community, is now at risk of being obliterated by a proposed retail and housing development.… The 1900 Fourth Street project would tower six stories high and excavate two acres of land for a basement parking garage. Ohlone family bands have joined together in steadfast opposition to the desecration of their sacred grounds and are leading a broadly-based community campaign to preserve the land.

In March of 2018, developer Blake Griggs Properties announced a new plan to force the City of Berkeley to approve a redesigned, enlarged 1900 Fourth project by exploiting a brand new state law designed to address California’s housing shortages. Under this law, 1900 Fourth could be approved in as little as 180 days with no environmental review or public process—silencing the public, steamrolling the will and voices of Ohlone people, and destroying what remains of a sacred site where human burials are likely interred.

Ohlone family bands and a broad coalition of Bay Area community members have vowed to not allow this grievous injustice to occur. We ask you to stand with us.

A ceremonial center of the Ohlone people

“We need to continue our obligations that were given to us by our ancestors to sing there, to pray there, to have communication. Our spirituality is not based in churches and in buildings—it is place based.”

—Corrina Gould, Chochenyo Ohlone

For today’s Chochenyo Ohlone community, the property at 1900 Fourth Street represents a living link to countless generations of their ancestors. Despite being covered by asphalt, this last 2.2 acres of open land continues to function as an anchoring place of community prayer and ceremony, critical to the cultural survival of a people who are recovering from 200 years of genocidal policies under Spanish, Mexican and American rule.

“Taking away our sacred sites is putting that last nail in the coffin,” Corrina Gould of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan explains. “It is wiping away our people.”

Three Ohlone family bands—Confederated Villages of Lisjan, Him’re-n Ohlone, and Medina Family—have described the great religious and cultural importance of the West Berkeley Shellmound and Village site in their cosmology and their vision for survival. They have also taken a resolute position that any potential further disturbance of their ancestors’ graves is not acceptable.

“Sacred ground is something to be honored, cherished, and above all else, protected,” Chochenyo Ohlone tribal member Victoria Robins says. “It is what makes our history rich, and connects us to our past. It reminds us of who we are and helps keep our culture alive. Without it, we are nothing.”

Ohlone people possess “the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites,” according to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Article 25), adopted by the City of Berkeley as municipal policy in 2015. By resolution, Berkeley also affirmed the UN Declaration standard of “ free, prior and informed consent of the Ohlone” specifically with regard to “any alteration planning for the Berkeley Shellmound sacred site.”

Ohlone leaders view their heritage site, which was designated as a Berkeley City Landmark in 2000, as relevant to all people, not just their own community. “It’s not just for the Ohlone people, it’s not just a ceremonial place where we pray, but a place the Bay Area in general can be proud of, as the oldest place people ever lived here,” says Corrina Gould. “It’s a wonder of the world, a place we should preserve.”

A landmark of international significance

“Once you destroy it, the window to that whole world—the first human habitation around the bay, and how they adapted to it—will be shut forever, and we’ll never know it. There’s no getting it back.”

—Richard Schwartz, Berkeley Historian

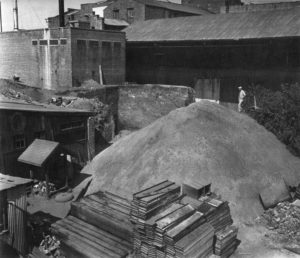

For thousands of years, the people of this original village on the East Bay shore thrived on the abundant resources of land and sea, developing a sophisticated maritime culture. Towering over the village was a great mound, estimated to have been at least 20 feet high and hundreds of feet long, one of the largest of the 425 shellmound funerary monuments that once lined the shores of San Francisco Bay. These mounds are older than the pyramids in Egypt and most of the major cities in the world.

Archaeologists have long recognized the importance of the West Berkeley Shellmound site, also known as the “West Berkeley Site,” or CA-ALA-307. The site has been determined eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under all four criteria, and is listed on the California Register of Historical Resources. Archaeological evidence from the West Berkeley Site has fundamentally shaped understandings of the early human history of the San Francisco Bay Area, and ongoing research continues to enrich and reinterpret an amazing historical narrative.

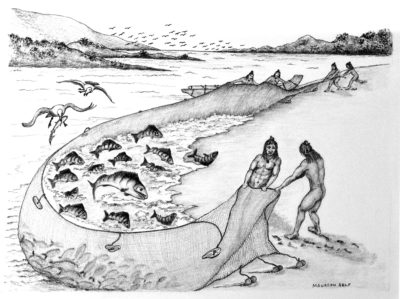

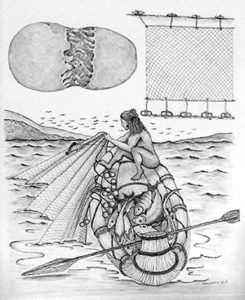

Eminent UC Berkeley archaeologist Kent Lightfoot describes the West Berkeley Site as a fishing village where “an active port was maintained over hundreds of years,” with dozens of tule balsa canoes going out on fishing and hunting expeditions, or ferrying people and goods across the Bay. Large nets were used to catch fish such as sturgeon, salmon, thresher sharks, jacksmelt and surfperch. Hunters pursued antelope, deer, tule elk, dolphins, porpoises, otters, sea birds and other quarry, cooking their catch in underground ovens and hearths.

A unique 40-foot long oval-shaped building at the site is thought to have functioned as a center for ceremonies, dances and special meetings. Charmstones, abalone pendants and other ritual items have been recovered from the site. Hundreds of human burials have been recorded, as well as ritual burials of coyotes and a California condor.

Today, after centuries of short-sighted development, nearly every square foot of this sacred heritage site has been dug up, leveled and covered over by buildings, roads and railroad tracks. This last open 2.2 acres of land at 1900 Fourth Street, currently the parking lot for Spenger’s Fish Grotto and local shoppers, is the only part of the ancestral village that remains intact below the surface and has never been built on. It represents a final opportunity to respect the original people of this land, restore a world heritage site, and reverse a shameful legacy of destruction, loss and erasure.

“I think this shellmound is the soul of Berkeley and that if Berkeley loses this, we lose our soul. We lose our sense of 5,000 years of history. This has to be stopped, because these are our origins. If we allow this ugly building to go up on the oldest village site, I don’t feel we deserve the respect of the world.”

—Malcolm Margolin, author of The Ohlone Way and founder of Heyday Books

Two years of public hearings and comment letters

Developer Blake Griggs Properties, doing business as West Berkeley Investors, first submitted plans for 1900 Fourth—a massive housing and retail development—in 2015. At that time, numerous Ohlone tribal representatives stated their opposition to any development on the property, and began organizing public interfaith prayer vigils for the protection of their sacred grounds. Blake Griggs pressed forward, and in 2016, began preparing an Environmental Impact Report for the original 1900 Fourth project, consisting of a five-story complex with 135 apartment units, 33,080 sq. ft. of retail space, and a parking garage.

Once the Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) for 1900 Fourth was released in November 2016, city inboxes filled up with a multitude of letters and emails in opposition to the project. These letters from concerned local residents, tribal members, historic preservationists, civic leaders, scholars and professional archaeologists presented many well-founded challenges to the adequacy of the DEIR’s methodology and findings.

Meanwhile, a series of public hearings regarding 1900 Fourth were held by Berkeley’s Zoning Adjustments Board and Landmarks Preservation Commission. Each hearing was packed to capacity with concerned members of the public who spoke passionately in favor of preserving the land for its cultural and historical value, taking aim at the DEIR’s claims that impacts to cultural and historical resources resulting from the project could be reduced to an “insignificant” level through any type of mitigation.

By a unanimous 8-0 vote on February 2, 2017, the Berkeley Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that “the DEIR (Draft Environmental Impact Report) is seriously deficient in content, scope, and findings.” The commission further recommended, “the Cultural Resources section of the document in particular be withdrawn, re-written, and recirculated.”

In fall of 2017, representatives of three autonomous Ohlone family bands—the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, Him’re-n Ohlone, and Medina Family—accepted an invitation to sit down with representatives of the developers to discuss the 1900 Fourth project. During these talks, Blake Griggs made offers that included reducing the project size and donating a portion of the property to the Ohlone groups, however, all offers were contingent on Ohlone approval of excavation and development on the majority of the site.

After representatives of the three bands conferred with their tribal and family members, carefully weighing the options, they reached a unanimous decision. In a public statement on December 19, 2017, the Ohlone groups declared their agreement to “unequivocally oppose any development that involves the desecration of our sacred site and the disturbance of our Ohlone ancestors. This includes our opposition to a ‘limited’ or ‘alternative’ development of the sacred site.”

Exasperated by growing obstacles and mounting opposition to their proposed project, developer Blake Griggs retained environmental law attorney and anti-CEQA crusader Jennifer L Hernandez of Holland & Knight, who fired off a 12-page threat letter to the City of Berkeley on January 22, 2018. Reiterating falsehoods about the nature of the project site, the letter claims “the only legal option available to the City is to certify the EIR with a finding of no significant impact to tribal cultural resources.” The letter further alleges that “the Applicant is legally entitled to a permit,” that the City has no basis for warranting re-circulation of the DEIR, and that if the City were to prohibit development on the project site, the developer would “seek appropriate legal relief against the City.”

“Nothing of any significance whatsoever”

Landowner Ruegg & Ellsworth and developer Blake Griggs were keenly aware from the beginning that the major obstacle to project approval would be the location of the property, squarely within the established boundaries of a highly significant state-registered archaeological site and the city-landmarked West Berkeley Shellmound site. To overcome this obstacle, Blake Griggs and their team of hired lawyers and PR consultants set out to strategically deny, diminish and discredit the cultural significance of the property.

The developer’s approach hinges on interpreting the West Berkeley Shellmound site in the narrowest possible terms, by isolating the historic mound itself, which is only one feature of the landmarked and registered archaeological and cultural site CA-ALA-307. The Ohlone community, archaeologists, and most members of the public typically refer to the entire village and cultural site by its best known and generic name, the “West Berkeley Shellmound.” As archaeologist Christopher Dore observes, “This is just a ‘shortcut’ name for this entire historical resource.”

Focusing on this narrow, self-serving definition of the cultural, historic resource, the developer then hired consultants to produce data supporting their predetermined conclusion that the shellmound itself was not located on the 1900 Fourth property. Despite a large body of evidence and previous archaeological work that had already established that the project parcel is fully within the boundaries of the site, an archaeological firm of questionable qualifications, Archeo-Tec, Inc, was brought in to selectively survey the site for evidence of the shellmound feature.

Using inappropriate sampling methodology and design that was based on a selective reading of prior archaeological data, Archeo-Tec surveyed portions of the property in 2014, finding shell fragments but not encountering the shellmound itself. As independent Bay Area archaeologist Christopher Dore observed in his March 2017 letter to the City, “such a strategy would not be expected to identify deposits.” Archeo-Tec’s report concluded with an unsubstantiated and confounding opinion that the likelihood of significant cultural materials on the site is “quite low.”

“I feel that the Archeo-Tec report is flawed,” Registered Professional Archaeologist Stephen Bryne, who conducted archaeological work at the West Berkeley Site on behalf of the city in 2001-2, stated in his comment letter on the DEIR. “The Archeo-Tec (2014) report, while it appears to support the [1900 Fourth] project, does not agree with nearly all of the earlier archaeological findings, including Archeo-Tec’s own (2012) results, regarding this important prehistoric site.”

Based on Archeo-Tec’s report, Blake Griggs Properties began making extraordinary claims that the site in fact contained no significant cultural resources of any kind. “There is nothing at all of any cultural or historical significance on this property whatsoever,” Lauren Seaver, Vice President of Development for Blake Griggs Properties, stated during a March 8, 2018 press conference.

In fact, the archaeological record strongly suggests that human burials and significant cultural materials exist on the project site. According to an extensive review of historical data and recorded sites in the vicinity by local historian Richard Schwartz, 455 human burials have been found within a 1-block radius of the property. “There are burials basically ringing the perimeter of the parking lot,” Schwartz states. Most recently, in 2016, the remains of five Native American individuals were encountered and removed during trenching for the 1919 Fourth St. development, directly across the street from 1900 Fourth.

Archaeologist Christopher Dore’s comment letter on the 1900 Fourth project concludes that “given the archaeological and historical data demonstrating that a large number of human remains have, and continue to be, discovered within the boundaries of CA-ALA-307, the probability of human remains within the project parcel is high.” Dore also notes that significant archaeological deposits not directly associated with the shellmound feature itself have been documented beneath the streets on three sides immediately surrounding the project site. “These deposits have no less, and in fact may have more, archaeological significance than deposits from the shellmound itself. Given the inappropriate methods used to investigate potential deposits within the project area, the probability is high that such deposits do exist but were not located.”

By focusing on what “has not” been found on the property, the developers deliberately deflect attention from the large body of archaeological evidence that places the property at 1900 Fourth St. right in the middle of the demarcated boundaries of the West Berkeley Site and its rich complex of cultural materials and human burials. And importantly, despite its surface being paved, the 1900 Fourth St. property is the only major portion of the site that hasn’t been significantly excavated and disturbed to date.

While the archaeological evidence is important, it is only part of the equation of determining what places warrant protection. The Ohlone community strongly asserts that they are the only ones with the authority to determine what is or is not sacred or culturally significant to them, and they deem that the entire cultural landscape of the shellmound and village site is sacred. “Just because they have dug around and created little potholes and things inside of this one area doesn’t make it less sacred and does not give the developer the right to tell us where sacred places are,” Corrina Gould states.

Exploiting the housing crisis: The new 1900 Fourth

On March 8, 2018, Blake Griggs held a surprise press conference in Emeryville, announcing a shocking new plan for strong-arming approval of an enlarged 1900 Fourth project by invoking a new state law designed to address statewide housing shortages.

Senate Bill 35, introduced by Senator Scott Wiener (D, San Francisco), targets localities such as Berkeley that are failing to meet regional housing needs, forcing local authorities to provide streamlined, over-the counter approval within 180 days for new housing projects that meet specific requirements. Local regulatory authority, public review or hearings, and even key state-level protections under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) do not apply if a project meets the terms of SB 35.

Blake Griggs seized on the opportunity to apply for streamlined approval under SB 35 by redesigning the 1900 Fourth project to meet the stipulations of the new law. The newly submitted 1900 Fourth project is dramatically larger, at 260 housing units—up from 135 in the original proposal—and adds a sixth story as well as an underground parking garage, which would require deeper excavation. To meet SB 35 criteria, 50% of the proposed housing units are so-called “affordable,” up from the 10% they were obligated to include in the original project. The affordability standard is low, defined as affordable for people who earn 80% of AMI (area median income) or about $80,400 for a family of four.

In statements to the press, Blake Griggs representatives describe the new 1900 Fourth project as providing great public benefit, and ironically attempt to portray themselves as champions of affordable housing who are concerned about the economic woes of teachers, firefighters and service workers. In reality, Blake Griggs is a for-profit corporation that simply re-branded its product and upped the number of planned affordable units because it was economically expedient to do so. To give new life to a beleaguered, failing project, Blake Griggs is attempting to co-opt political momentum from the statewide movement for affordable housing.

Attorneys working on behalf of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan dispute the developer’s claim that 1900 Fourth meets the requirements of SB 35. Under the provisions of SB 35, a project is disqualified if it is on a site where development would result in the demolition of a “historic structure that was placed on a national, state, or local historic register.” Historic structure, in state and national historic preservation case law, is broadly defined and includes earthworks, paths, mounds, and “land that has been landmarked by the local government,” such as the West Berkeley Shellmound Landmark. Attorneys for the city of Berkeley are currently reviewing the developer’s application and will determine by June 5, 2018 if it meets SB 35 requirements.

Regardless of the intended merits of SB 35, the actual effect of the law in this case would be to silence the voices of the public regarding a project that has been widely contested, to steamroll the will and the sovereign rights of Ohlone peoples and the legal obligation to consult them, and to completely nullify the hundreds of hours that members of the public have spent attending hearings and submitting comment letters.

“Ohlone people are not against development or affordable housing in our homelands, especially in this time of great need,” says Corrina Gould. “But this is the very first site of our ancestors along the Bay, and it needs to be protected — for Ohlone people and everyone that lives on this land. There are other sites that would be appropriate for new housing.”

An Ohlone vision for the land

While standing steadfast against the desecration of the West Berkeley Shellmound and Village Site, Ohlone leaders have also advanced a vision of how the 2.2 acre property at 1900 Fourth Street could become once again the monument to their ancestors that the great shellmound once was—a touchstone through which all people who reside in or pass through the Bay Area could learn about the true history of this land.

To that end, Ohlone people have presented a proposal for how the property, currently covered by asphalt, could be transformed into a natural open space area—a memorial to thousands of years of habitation by Ohlone people in Berkeley and a tribute to their survival today. “We envision a living cultural space—revitalizing cultural traditions, like songs, language and dances,” says Corrina Gould.

“The proposed development is a huge complex that would obliterate anything that we could use as a sacred place,” Gould observes. “It’s important for the public to see the opportunity to begin to dream about what it could be other than a retail space and housing.”

To learn more about alternatives to housing development, visit our Ohlone Vision for the Land page.

A responsibility to future generations

Bay Area News Group

Bay Area News Group

“It’s not too late to save this one piece of ground, this one place that doesn’t have building, this one place that is open to the sky.” —Corrina Gould

While other sites with remnants of pre-European habitation exist elsewhere in Berkeley, local author Malcolm Margolin observes that “there is no other place that connects us as fully or as deeply to the long Ohlone past” as the West Berkeley Shellmound.

And most importantly, this last open ground at the West Berkeley Shellmound site is a critical touchstone for the Ohlone community in their continuing struggle to survive, culturally, in the 21st century. It is a place where future generations of Ohlone people can come to remember, to connect with their ancestors and to know who they are.

“I have a responsibility to stand my ground in this way because I have children and I now have grandchildren,” Corrina Gould explains. “If we lose these places where we’re supposed to pray and sing, then we lose who we are, and the entire genocide is complete. Our grandchildren have a right to know who they are and to be planted firmly in this land. It’s my responsibility to ensure that they have a future, here in our own territory.”

“When will enough be enough?” Vincent Medina, a young Chochenyo man, asks. “How long will our community have to suffer this disrespect and continued injustice? Our cultural heritage should not be disrespected and removed from the earth, and our sacred and religious sites should not be desecrated. I ask you to stand with us—all Chochenyo Ohlone people who are here in this land.”

The developers intend to break ground in 2019. Ohlone people have made it clear they will not accept the desecration of the sacred grounds of their ancestors. It is the responsibility of everyone who cares about our common human heritage and believes in respecting the rights of indigenous peoples to not allow this injustice to proceed. Please stand with us. ☆